The Darzi report confirmed what most people involved in or close to the NHS already know: there is increasingly high spending directed into the vortex of acute care, accompanied by declining productivity, under-investment in technology, and the constant, counter-productive raiding of capital budgets.

The demands of operational performance and financial pressures dominate the headspace of NHS leaders. In contrast, there is a relative decline in funding for primary and community services, prevention, and public health. This trend is the opposite of what the NHS needs. Instead, the focus should be on increasing productivity and improving patient outcomes, with a much greater emphasis on care outside hospitals, prevention, and equity.

In discussions around improving performance and productivity, health inequalities are often sidelined. Financial and operational productivity issues are addressed in different spheres and settings than those focusing on population health, prevention, and health inequalities – or, at best, they are separate items on the agenda.

However, if the NHS, in partnership with Local Government and the VCFSE sector (Voluntary, Community, Faith, and Social Enterprise), is to truly shift this trend, the value of prevention and addressing health and healthcare inequalities needs to be central to driving greater productivity as well as ensuring more equitable access, experiences, and outcomes. This is not just due to the 'moral imperative' of reducing health inequalities—unfair and avoidable differences in health between groups—but because a population health and inequalities-focused approach to health and care is also better for financial health, as well as patient health and equity.

A common misconception, even myth, is that preventive and public health interventions take a long time to deliver benefits. While this can be true of some social determinants of health (such as housing, income, employment, the environment, and structural racism) and more immediate causes of poor health (including diet, lack of exercise, alcohol, and gambling), there are many highly cost-effective health interventions that have short- to medium-term beneficial impacts—for both health and finances.

Here is a selection of key interventions, grouped under two headings—focused interventions and more generalised services—along with their main short- to medium-term health and financial benefits:

Focused Interventions:

- High Intensity User services: These services focus on people who frequently attend A&E. They can reduce A&E attendance and non-elective admissions by up to 84%. These non-clinical services provide personalised support to understand the reasons behind repeat visits to A&E.

- CVD prevention - blood pressure checks: Hypertension is a key risk factor for CVD and affects 1 in 4 adults, half of whom are undiagnosed or have uncontrolled blood pressure. Lowering blood pressure by 10mmHg can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by 17%, stroke by 27%, heart failure by 28%, and all-cause mortality by 13% (Ettehad, 2016). One innovative example is Bharani Medical Centre in Slough, which proactively improved its control rates.

- Smoking cessation: The NHS can play a key role in smoking cessation, such as the Secondary Care 'CURE' programme in Greater Manchester, with a whole section on evidence here, which has demonstrated reductions in both acute readmissions and length of stay.

- Increasing vaccination uptake: Increasing the uptake of vaccinations among vulnerable groups helps to moderate downstream care needs and admissions, such as for flu, COVID-19, and MMR in children and adolescents.

- Early cancer diagnosis: Early diagnosis is one of the best ways to lower cancer-related deaths. However, large disparities exist between ethnic groups in screening uptake. Increasing screening among the black community.

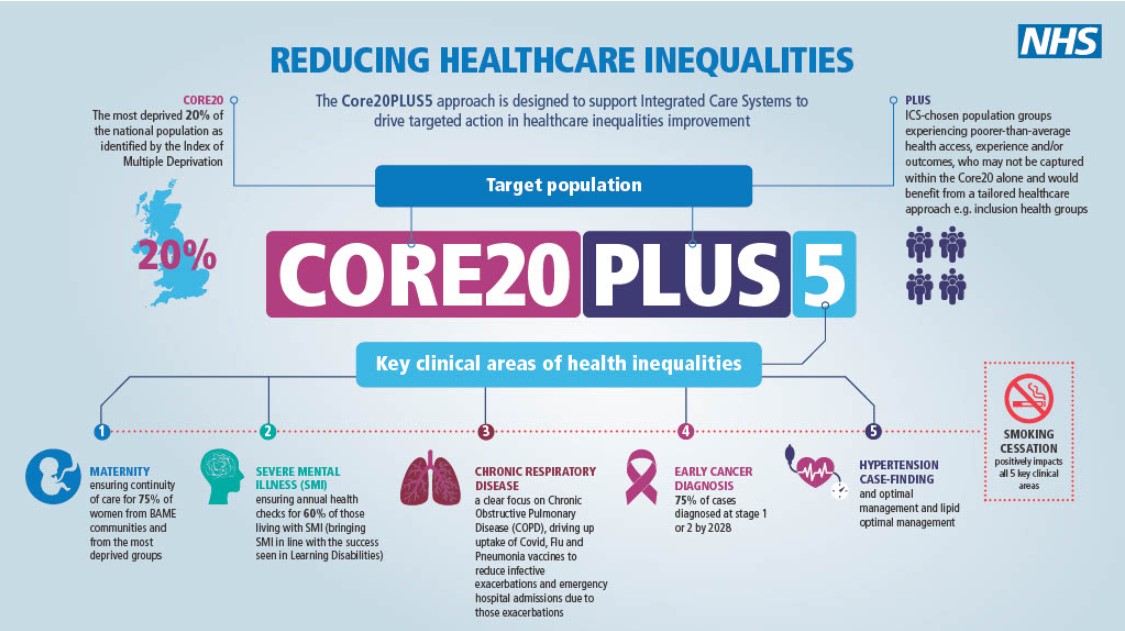

Many of these interventions are included in the adults version of Core20PLUS5 due to their evidence-based impact and benefits, targeting the most deprived and excluded communities.

While many of these activities and interventions already exist across health and care systems, they are not yet implemented at the scale needed to make a deep impact on prevention, health equity, and financial improvement. Many programmes and services also suffer from short-term funding and lack sustainability, despite evidence of their impact.

More Generalised Interventions (targeting excluded communities – where the health outcome benefits are more extensive):

- Social prescribing: Social prescribing helps reduce loneliness and poor mental health by linking patients with non-medical support within their community, such as charities and voluntary groups. There is a strong economic case for this approach. The economic case for Social Prescribing.

- Community health and wellbeing workers (CHWW): Local pilots of this targeted health outreach model have shown significant results. For example, the Westminster programme demonstrated increased vaccination and screening rates and a 7% drop in unscheduled GP visits in the first year. CHWWs reduced demand while finding those who need care but do not seek it.

- Tackling health inequalities at the household level: This involves increasing vaccination uptake and health checks for diabetes and hypertension.

Focusing on communities and households most affected by deprivation and exclusion will greatly benefit from more investment in community-based approaches, with strong support for the voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise (VCFSE) sector. Greater engagement and co-production with local people reflect a more progressive and sustainable model for health and care, as exemplified by New Local's Community Powered Health and Care.

Conclusion:

In closing, I recommend three highly valuable resources related to health and equity, which offer well-evidenced recommendations for NHS organisations working with local partners—across Integrated Care Systems, Place-based Partnerships, Providers, and, crucially, Primary Care Networks and Neighbourhood team level:

- Tackling health inequalities: seven priorities for the NHS - The King's Fund

Alongside the moral case for action on tackling inequalities and the worst health outcomes, there is an economic case: a more equitable NHS is likely to be more efficient. Reducing the barriers to accessing services will prevent ill health, while tackling racism and discrimination will help to recruit and retain staff in the NHS. This will also support the government’s aim of helping more people out of long-term sick leave and bolstering economic activity.

The cost of failing to put prevention first can be seen across all areas of public services – and results in higher acute demand for other public services, not just the NHS. Failing to invest in prevention not only costs the economy, it also results in loss of opportunities for people and loss of life.

- Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities: main report - Public Health England, 2021

The context and causes of health inequalities highlights the multiple causes of health inequalities which are complex, interactive and simultaneous in their combined actions, with their roots in the wider determinants of health.

A joined-up approach that treats the ‘place’, and not just individual problems or issues, is therefore necessary if we are to measurably reduce inequalities in health and wellbeing.

The great work led by Professor Chris Bentley on Place-Based Approaches strongly supports the idea that targeted health interventions in key areas, including hypertension, CHD, diabetes, and cancer, can yield short- to medium-term benefits, often within three years.

These resources guide NHS finance and related professionals on improving health equity and making a case for funding prevention and inequalities-focused programmes.

Things may be looking up. Despite economic pressures, the new Labour government seems committed to the 'three shifts,' which will include renewed investment in upstream prevention. Health ministers are pressing the Treasury to fund 'a lot of prevention projects’.

Read more about NHS SCW's work on Health Improvement and Inequalities